The threat of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and the challenges of cleaning it

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch was first discovered in 1997 by Charles Moore, a scientist with a passion for the ocean who has spent much of his life on the water and studying how to better preserve the seas.

On his way back to California after participating in the Trans-Pac Yacht Race — which traverses the Pacific from Los Angeles to Honolulu — Moore noticed the pollution. On his website, Moore describes the shocking encounter, “I could stand on deck for five minutes seeing nothing but the detritus of civilization in the remotest part of the great Pacific Ocean.”

Sadly, despite increased awareness of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, the problem persists two decades after its discovery. This is not due to lack of concern. The multi-faceted problem, which scourges 600,000 square miles of the Pacific, requires multiple solutions — none of them simple.

The Plastic Vortex

Researchers discussing the Garbage Patch are much more likely to use the term Plastic Vortex. The idea of a “patch” makes it sound to some like there is a floating island of trash in the middle of the Pacific when the reality of it is more complex.

Earth’s oceans have five major gyres: the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (the location of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch); the South Pacific Subtropical Gyre; the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre; the South Atlantic Subtropical Gyre; and the Indian Ocean Subtropical Gyre.

Each gyre is a place in the ocean where several rotating currents swirl around a central point. Much like drains, gyres swirl clockwise north of the equator and counterclockwise south of it. These gyres do not stay in one spot in the ocean; they spin their way across miles of sea, accumulating debris along the way.

Knowing how the gyres travel, it’s easy to understand why researchers prefer to describe the situation as a Plastic Vortex rather than a Garbage Patch.

A Contaminated Food Chain

Plastic stuck in the vortex is far from harmless. A 2011 study by UC San Diego examined fish in a 1,700 mile span of the Plastic Vortex and found plastic in 9.2 percent of them.

Going by those numbers, it’s estimated that fish in the North Pacific eat between 12,000 and 24,000 tons of plastic per year. Chances are, the numbers skew to the higher end of that estimate since there is approximately six times as much plastic in the Plastic Vortex as there is plankton — and fish can’t tell the difference between the two.

The ingestion of plastic by marine life is also a human health issue as plastic and its contaminants work their way up the food chain to our dinner plates. Plastic is known to absorb carcinogens like DDT and PCBs which are then released as the plastics break down.

Scratching the Surface

Project Kaisei, founded in 2009, is a collection of scientists that has set out to study and clean the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Their focus is to catch plastic safely, without harming sea life, and bring it back to shore where it can be recycled into new plastic, fuel, or apparel.

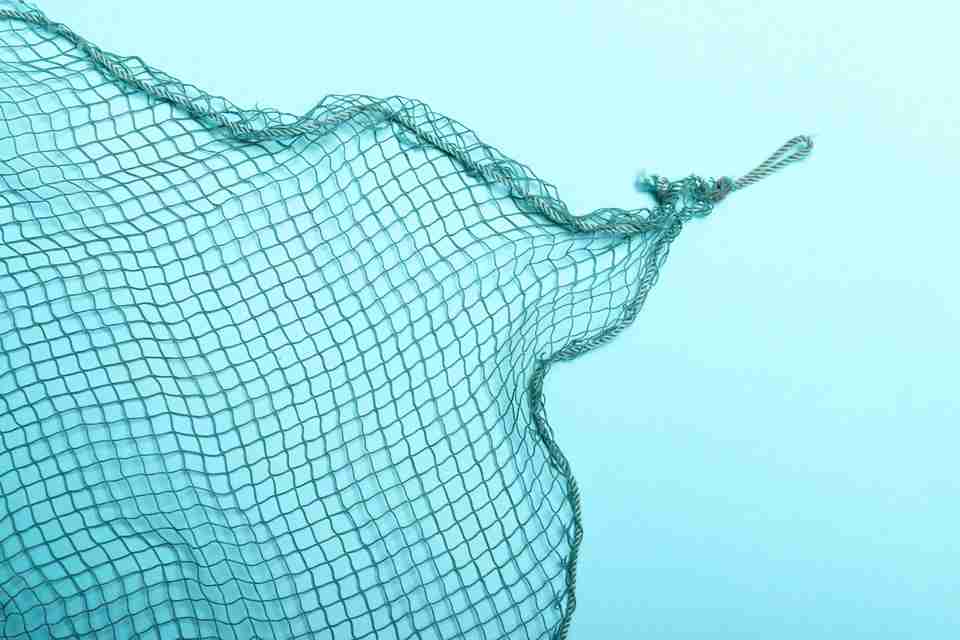

In its effort to clean the Plastic Vortex, Project Kasei classified four distinct types of debris found in the ocean and ways to clean up each. The largest debris type is “ghost nets,” abandoned fishing equipment weighing anywhere from 300 pounds to five tons. This trash can be removed by tug boats, cranes, and barges. The next largest type is “floating consumer plastics” — buckets, laundry detergent bottles, fenders, etc. — which can potentially be picked up by fishermen who see them floating in the sea.

Smaller plastics and crushed pieces including plastic toothbrushes, toys, and larger plastics that have been crushed at waste disposal facilities make up the next group which Project Kaisei believes can be picked up by oil skimmers when they are not deployed cleaning up a spill.

The smallest, most challenging group to clean is microplastics, the removal of which Project Kaisei is hoping to resolve by looking into the creation of biomimicry devices.

A Tubular Solution

In September The Ocean Cleanup was launched in the latest, most comprehensive and technologically advanced effort to clean the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The brainchild of Dutch inventor Boyan Slat — who came up with the idea in 2015 at the age of 20 — has been compared to a Pac-Man device that will roam the garbage patch, funneling plastic to its center which is then taken away by boats acting as garbage men.

The Ocean Cleanup is a 2,000-feet long tube fitted with a 10-feet deep skirt that tapers off towards the ends and collects plastic. The tapering of the skirt at the end creates more resistance, causing it to lag behind, giving the device its u-shaped “mouth.”

The tube moves naturally through the water, propelled by winds and waves which carry it faster than the skirt and oceanic plastic which are carried by the oceans currents. This difference in speed is what allows the plastic to accumulate in the net. A downward flow created by the net allows sea life to safely swim under the 10-foot net.

The Ocean Cleanup is equipped with solar-powered lights, cameras, sensors, satellite antennas, and navigation modules, allowing it to be constantly monitored in terms of location and performance. Its modular assembly means that the design can be further refined or scaled up as its work necessitates.

In all, The Ocean Cleanup hopes to deploy 60 such vessels and clean as much as 50 percent of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch every five years.

The Deeper Problem

The devices used by The Ocean Cleanup may well be successful in cleaning up large portions of the Plastic Vortex, but the problem remains in microplastics which can slip through even the tiny holes in its mesh. Additionally, not all plastic floats and collects at the surface and tiny pieces that break down can sink down the water column, some of it eventually ending up on the ocean floor.

Small pieces of plastic, whether at the surface or part of the ocean sediment, can be just as dangerous as bigger pieces. Tiny ocean animals at the bottom of the food chain can consume microplastics, sending it on its way up the food chain as they become prey.

While we wait on something like Project Kaisei’s biomimicry devices to clean up microplastics in the ocean, the best way to prevent the further growth of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and other such pollution in the five gyres will be done on land. Putting infrastructure in place that prevents plastic from ever entering the ocean is one way to start. Another is examining consumer habits that contribute to the problem—including the proliferation of single-use plastics—and seeing where changes can be made.